Your Cart is Empty

Author: Logan Hayes

A QUICK-START REFERENCE GUIDE TO PU'ER TEA

The information here was collected during our travels and through working directly with the many, many people involved in making pu’er tea. Emphasis on the many! It took dozens of people—field hands, a team of producers, a small army of wrapping personnel—to make our first line of tea cakes come to life. To help make sense of those and bring clarity to this poorly understood genre of tea, we set out to distill this vast world into a useful, easily understood blog post, and give pu’er the transparency treatment à la Hugo.

All that said, where do we start?

Well, pu’er is a type of tea. It’s made in Yunnan province, China (and the northerly areas of border nations Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam). It’s probably about 2,000 years old, but is at least 1,500 years old, when we have records proving pu’er was traded along the Tea Horse Road, a network of paths connecting Yunnan, Sichuan, and Tibet. The city of Pu’er (also called Simao) in central Yunnan was the center of this trade, and early on the teas adopted its name. Today, pu’er is much the same: a traded commodity. But its popularity has only grown. So much so that it’s the only tea with enough market influence to have experienced a genuine boom and bust!

Where it's made?

If you know us, you know we subscribe to this newfangled idea that any tea can be made anywhere. Not so with pu’er. There are many reasons: no real pu’er expertise outside Yunnan, the indigenous tree varietals don’t thrive outside a subtropical climate, etc. But most importantly, nothing happens in this world without economic motivation, and there is simply no demand for copycat pu’er. The domestic market is strong. So it’s been made in once place since recorded history: Xishuangbanna. Pinched between Myanmar and Laos, ‘Banna is host to the world’s oldest and most celebrated tea forests. And yes, they are forests!

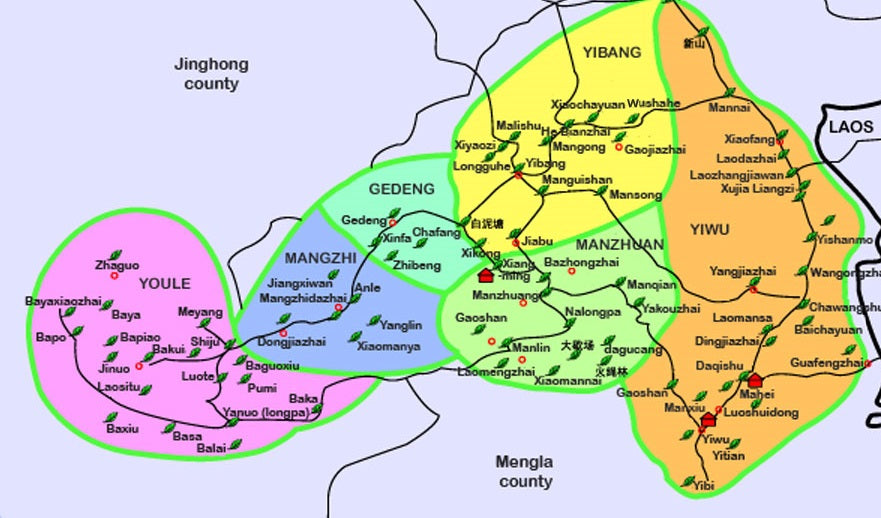

Cutting right down the middle is the Lancang river, which divides two sets of “famous” tea mountains (among the many dozens). On the east, you have the 6 “old” mountains. They are:

| Yiwu shan

| Gedeng shan

| Youle shan

| Yibang shan

| Mangzhi shan

| Manzhuan shan

Shan = mountain, which you’ll want to know when buying pu’er. All our cakescome from this side of the river, which is also loosely considered “Yiwu area” tea, no matter the specific mountain.

West of the Lancang are the 6 “new” mountains. (Though neither side is older or newer than the other; “new” is just an expansion of the “most famous mountains” list). They are:

| Nannuo shan

| Jingmai shan

| Bulang shan

| Mengsong shan

| Manqiao shan

| Bada shan

As you can see, there are an incredible number of other mountains, all of which bring a distinct quality to the teas they produce, owing mostly to their individual terroirs.

What is terroir, anyway? Land, essentially. A word often used in wine, coffee, and tea to discuss soil quality, weather, biodiversity, and other environmental factors that ultimately influence the final character of an agricultural product. It's a thing for all types of tea, but pu'er especially—from what mountain the tea came is a critical piece of info.

So with pu’er, we concede, where it’s made is at least as important as how. And it’s not just about terroir; the age of the tea trees, their elevation, and their exact genetic makeup are all crucial elements that make a pu’er what it is. Most of the geographic features integral to good pu’er making are only found in Xishaungbanna.

Generally—and this is not a hard rule—Yiwu area tea is known to be softer, sweeter, lighter in some respects, while west of the river teas are punchier, bolder, perhaps more complex. Some specific mountains impart an unmistakable flavor; Bulang shan teas are characteristically bitter, for instance.

Why is this done at all? Originally, for ease of transport. Along that Tea Horse Road we mentioned, mules could carry a whopping 60 kg of tea. But loose tea took up way too much space, so it was formed into tightly compressed, 357 gram shapes, and then packed into "tongs" (small towers of 5-7 cakes wrapped in bamboo leaf), to make 2.5 kg packages of tea. All this is still done today, even though pu'er usually commutes by truck, boat or plane, and modern cakes usually come in 200 gram forms.

HOW TO ENJOY IT?

The beautiful thing about pu’er? Steeping it is a cake walk. Despite all its complexity, one of the most acceptable methods of preparation is grandpa style. This sees a chunk of tea popped into a mug, topped with hot water, sipped down ’til about 1/3 of liquid is left, and topped off again. Rinse and repeat until the tea stops giving life. But won’t the tea leaf get into my mouth? Not really! These big, intact Yunnan tea leaves tend to sink and rest in the bottom of the cup. Anything that does float, just strain with your teeth. Simple as that. All you’ll need is a mug, and something to crack into the tea cake with (unless you’re using coins—in which case, just use the whole coin!).

Of course, pu’er tea’s many nuances are really only accessible through gongfu (click here for a step-by-step guide). The only extra gear you’ll need is a tea knife, a specialized tool specifically for tearing apart cakes without compromising the integrity of the leaves. Our house knife is coming soon, but for now, you can use any tool that resembles a pick (hell, even a clean flathead screwdriver works…not that we’ve tried that...)

EVALUATING PU'ER

Appreciating pu’er can take a bit of practice. For some—especially in the case of shou—it’s an acquired taste. Ultimately, taste is king. If you like the tea, the tea is good. On a deeper level, we can get some clue about the quality of a pu’er based on these factors:

Aroma:

If it’s sheng pu’er, we’re looking for bright aromas of banana peel, incense, and complex florality on the dry leaf. No matter what it smells like, strength of aroma is a good indicator that the tea has a lot to offer. With shou on the other hand…you want hints of camphor, cinnamon, tree bark, dark beer, and other “deep” aromas. What you don’t want is wo dui (“wet piling”, the process we outlined earlier), also called pile scent. This presents as musky, fermented, and downright fishy. 1-2 years’ age usually sheds this from shou, but low quality productions will have a persistent marine quality that is a major red flag. Pass on a shou if it’s reminding you of fresh-caught trout.

Appearance:

The look of the leaf will explain a great deal about any tea. For compressed teas, look first for leaf integrity—are you seeing large, well-formed leaves, twisting and weaving throughout the cake, or are you seeing what looks more like chopped up spinach (sheng) or coarsely ground coffee (shou)? Beyond that, look for lighter streaks in the tea (in sheng these look more white, in shou they’re more orange)—these are tea buds/tips, a more desirable bit of material that imparts sweetness and body (true of any tea). The more, the better—but don’t expect it in huangpian, where the whole point is to use older leaf.

Body sensation:

We’ll keep this one short and sweet, as there is zero scientific study on this, but how a tea makes you feel can give you some idea of its quality. If you notice an uplifting sense of airiness and joviality after a few cups, you may be what’s called “tea drunk”. This is usually brought on by “cha qi”, or “tea energy”, a decidedly unobjective measurement of a tea’s effect on the body. Take this entire concept with several grains of salt, but drink a ton of old tree pu’er and you might become a believer.

Lastly—and by far most important—taste:

No matter what a pu’er smells or looks like, if it tastes good, it’s good. There are acquired (read: foul) flavors that are considered positive in the pu’er world (like extreme bitterness), but you don’t have to appreciate those to assess a pu’er as quality. In good sheng, you're liable to find pleasant tones of apricot, banana peel, and orchid, with shou giving spice, bark, or menthol. Huangpian might taste like a heartier sheng, dianhong like roses and chocolate, and yue guang bai like honey and hay. In all pu’er and pu'er-adjacent teas, sweetness (and especially lingering sweetness, called “hui gan”, which presents as a lasting, saliva-inducing sensation in the throat) is a virtue. Even in the varieties famed for their bitterness. Above all, if you keep coming back for more, it’s good tea. Trust your tongue.

LASTLY, A WORD ON STORAGE

There are two schools of thought on this, well-understood by folks much smarter than us whose actual job it is to store pu'er for the long-haul. But to give you a brief rundown, in case you want to speculate on the future value of our tea cakes and diversify your investment portfolio with tea:

Two Schools of Storage:

| Wet storage.

Practiced mostly in Hong Kong, this sees pu’er stored in hot, humid environments to encourage rapid aging. Sheng pu’er that has been wet-stored will indeed be distinct from its fresh counterpart, and bring something closer to shou to the table, but with more refinement.

| Dry storage.

Dry storage isn’t really dry at all—in fact, with truly dry storage (as in arid places like southern California) the total lack of humidity is liable to at best stall your tea’s aging, and at worst slowly stale it. Avoid fully dry environments if you want to store long-term. In the short-term—we’re talking a year or less—it doesn’t really matter how you store pu’er. Just don’t keep it next to that washed geisha that smells like pomegranate and blood orange.

Any tea can be wet or dry stored. The basic principles are to keep your tea in a reasonably humid environment, away from other scents, and at a high enough temperature for living organisms to do their thing. Oh, and do not refrigerate.

If you’re ambitious like that, you could build a “pumidor” (a play on the word humidor).

This article walks you through it.

IN SUM

That's about all you need to enjoy pu’er tea. As always, we’ve done our best to be fully transparent and share everything we know with you. But frankly, we’re still learning. We’ll make a regular thing out of sourcing pu’er and other Yunnanese teas, and share what we learn from our producers with you, but for now, these are the facts straight from the horse’s mouth. Use them well.