Your Cart is Empty

Author: Logan Hayes

Abstract:

Tea “typology” is the science of classifying tea. Tea is usually classified broadly by oxidation (green, yellow, white, oolong, black/red, fermented), and specifically by production methods within oxidation categories. A tea’s classification—or type, style, category, etc—is determined by many factors: oxidation level, production method, growing region, and others.

The Gist

All tea comes from the same plant. It’s a tree, in fact. White tea, green tea, all manner of oolong teas, and so on—all born of the same genus, Camellia Sinensis. Simple enough, but it’s a real mess to sort through from there. Cultivars, processing methods, origins, and the nearly infinite combinations thereof—they all make a tea what it is.

(We don’t always agree on what makes a tea, a tea—we believe any tea can come from anywhere, for instance, one of our more controversial stances—but categorizing is a mostly agreed upon soft science.)

So, how do we know what’s what?

Luckily, folks smarter than us have this stuff mostly figured out, and our close relationships with tea’s best and brightest gives us direct access to the most official perspectives on the subject. There are a few recurring themes in the reasons they give us that explain exactly why tea typology matters.

Why Classify?

We systematize tea to promote and provide tea education, guide our sourcing practice, and—this one’s Hugo specific—improve specialty tea understanding in the specialty coffee community.

But the larger purpose of classifying tea is manyfold:

| Market reasons. This isn’t the most pure or heartwarming reason, but it’s certainly the most influential in this industry. Mostly, tea is classified so its producers, distributors, and anyone else making a dime off these leaves can leverage their product to maximize profit. We have to be on top of market trends and their fluctuations to be effective tea importers—they help us understand why teas cost as much as they do, and sometimes, encourage us to help our producers experiment with foreign styles.

| Cultural reasons. There’s also hometown pride at play. Folks from Hangzhou, for instance, claim (rightfully) their homeland as the birthplace of longjing. So when it’s made elsewhere, well, that sometimes ruffles feathers.

| General education. This is the truest motive for us. We want you to be a better informed tea drinker, because this tea thing is more rewarding (and fun) when you understand what we’re talking about!

Now, onto the methodology:

TYPES OF CLASSIFICATION

| By oxidation | By processing | By origin / terroir)

Classifying by Oxidation

First up, we have the best understood tea classification method: by oxidation. If you didn’t know, teas become green, white, oolong, etc, in part based on how much we let them rot. Just as an apple browns when cut, teas do the same when plucked—and (except with green and yellow teas) producers let it happen on purpose! Sometimes, especially in the case of oolong, we help it along by smashing, rolling, or otherwise bruising tea leaves until they’ve sufficiently oxidized.

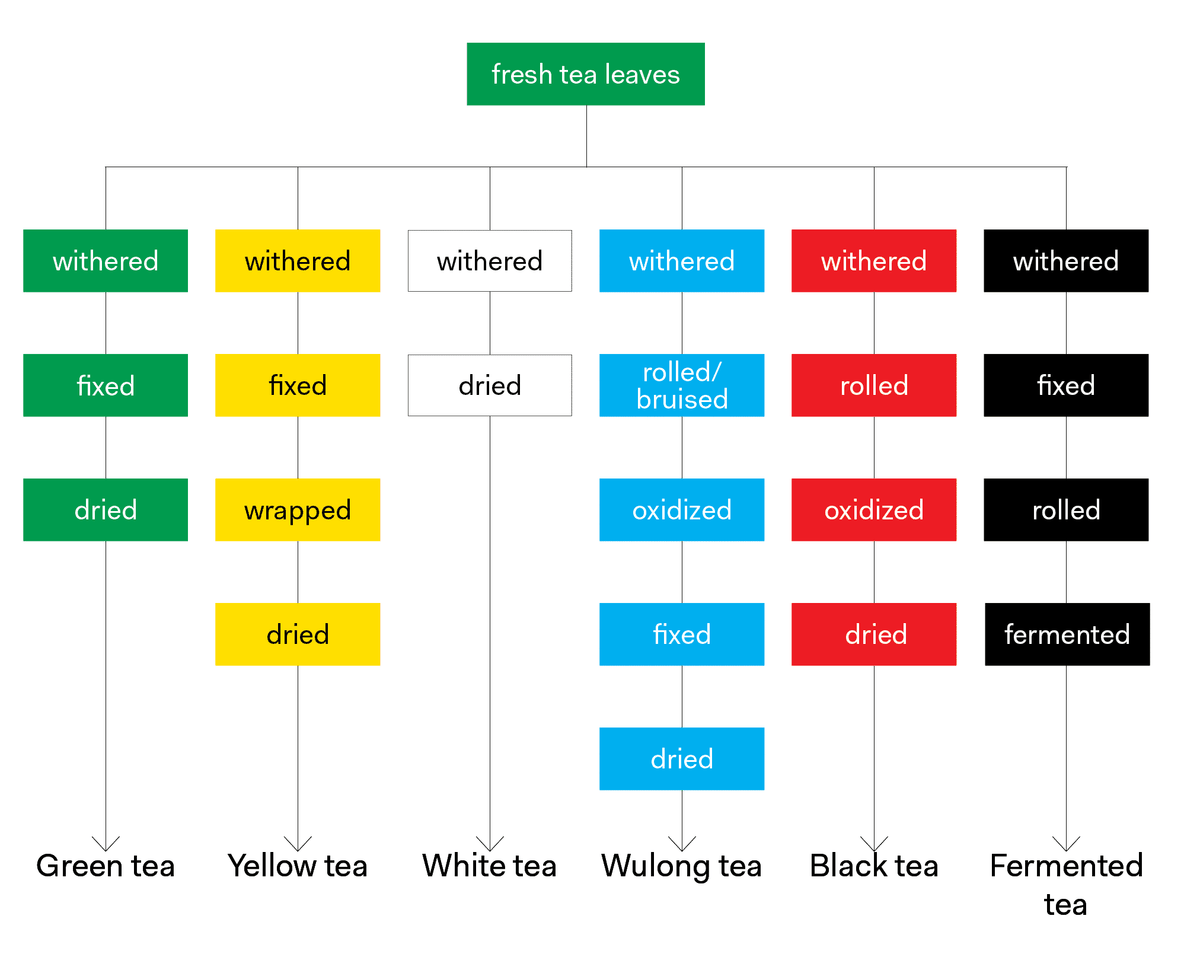

Our friend Tony Gebely (who’s blog you should poke through) breaks down tea processing in this handy chart.

Defining the above terms:

Withering — To dry fresh tea leaves, allowing moisture to evaporate. Can be done indoors or outdoors, usually on floor tarps or bamboo racks. For each tea (and each tea producer), this process will be different.

Fixing — Heating tea leaves to deactivate the enzymes responsible for oxidation. Also called “kill-green”, all teas except white undergo this process at some point, whether by steaming, pan-frying, baking, or some combination thereof.

Rolling/bruising — Shaping tea leaves (by hand or with machines) and simultaneously crushing/tearing them to encourage oxidation. How and how much this is done is a critical part of a tea’s identity.

Drying — Simple as that. Tea leaves can be dried in the sun, with fans, in ovens, over charcoal fires, and even with smoke!

Fermenting — Shou (“ripe”) pu’er and hei cha (“dark tea”) are post-fermented; that is, after all the above, these teas are rewet, piled, and allowed to further ferment.

The common thread in all tea processes is the extent of oxidation before the tea is fixed. Theoretically, unfixed white tea never stops oxidizing; but without processes to facilitate it, the going is slow (hence the popularity of aged white tea). Oolong,(Tony uses the Chinese “Wulong” above) is by far the most complex of the categories by oxidation, with a near infinite number of variable processes employed in its production. We haven’t counted, but there are probably nearly a hundred styles and subtypes of oolong tea. It's a useful example to segue into our preferred classification method that builds on the basic principles of Tony's chart:

CLASSIFYING BY PROCESSING

The above typifies tea into its most basic categories (by the processes that lead to its oxidation level), but what separates one oolong tea from another, for instance? All the rest of a tea's processing!

This method is our preference, as it helps us understand what makes the many subtypes of tea under the oxidation umbrellas so different from each other. Processing includes oxidation, but also all the other aspects of a tea’s production.

Take dancong, for instance—an oolong with literally dozens of riffs on itself. There’s the heavily oxidized mi lan xiang—taken to 60 or 70%, roughly, via rolling into spindles that are allowed to rest until the tea is blue-purple.

Then we have ya shi xiang, brought to around 35-45%, leaving the leaf more green-yellow. Why? In general, lighter oxidation produces lighter flavors; tart fruit, soapy florality, thinner body. It all has to do with what best suits the cultivar.

Both are dancong oolong, but in the case of ya shi xiang (literally "duck shit scent"), producers have known since its inception that the soapy florality and bright fruitiness of duck shit is best highlighted with lighter oxidation, and that mi lan xiang's deep honey and orchid character needs a heavier hand in oxidation. Great producers experiment (this fully oxidized black tea is of mi lan xiang cultivar leaves) but the time-tested methods are still employed for a reason.

So, while a tea's type is usually about oxidation level, it also considers leaf shaping, fixing method (most Japanese teas are steamed while most Chinese are pan-fired, for example), roast level, and other factors. They are simply too many to list, but understanding them is critical to being an informed tea drinker.

CLASSIFYING BY ORIGIN

Finally, we have classification by origin. This is usually secondary to oxidation and processing classification, only applying to known tea styles with established cultural and economic histories.

In general, we consider economic reasons for classifying tea by origin less valid than for reasons of predicting objective quality.

For example, it’s less important to us that dongfang meiren comes from Hsinchu, Taiwan, than it is that the right cultivar is used, tea jassids exist in the growth environment, and that the production is correct. Some teas—like zhengshan xiaozhong—more or less have to come from one place (the pine wood used to smoke that teaonly comes from Tongmu!), but for other teas, it’s market interests pushing the narrative that origin is critical.

Take yancha: you have zhengyan (“proper rock”) tea produced in Wuyi national park-proper, banyan (“half rock”) produced in the areas surrounding the park, and zhoucha (“island tea”) grown well outside the park. We source a fine example of yancha that flies in the face of this idea that zhengyan is unquestionably better. It’s higher elevation, grown in rocky soils, uses the same cultivars, is charcoal roasted, and otherwise produced exactly the same—so why is it valued exponentially lower than zhengyan yancha? Scarcity is one thing, but if these teas are indistinguishable on the cupping table, what are we paying for when we buy the “genuine article”?

Our thinking is thus: any tea can be made anywhere, under the right circumstances. It would be another thing to source off-brand tea and pretend it’s the real McCoy, but we're forthcoming about all our teas. For us, when classifying tea it's more important to understand the producer’s intent, know every intimate detail about a tea’s making, and be transparent with this information.